October 2016

AS THE RIM of the moon rose, huge and yellow, over the Caucasus, all of the dogs in the Georgian fortress town of Sighnagi and across the vast and dusty Alazani Valley began to howl. The howling continued until the bottom edge of the moon had cleared the highest ridge – and then the dogs suddenly fell silent together, as if somebody had thrown a switch.

The diners in the rooftop restaurant in Sighnagi had stopped talking to listen to the howling. When the noise ceased, they picked up their conversations again as if nothing had happened. It was just one of those things that make Georgia such a strangely affecting country.

The Republic of Georgia lies between the Greater Caucasus mountains in the north and the Lesser Caucasus in the south, providing a corridor from Batumi on the Black Sea to Baku in Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea. It is, and always will be, part of the Silk Road (although oil is rather more important than silk these days).

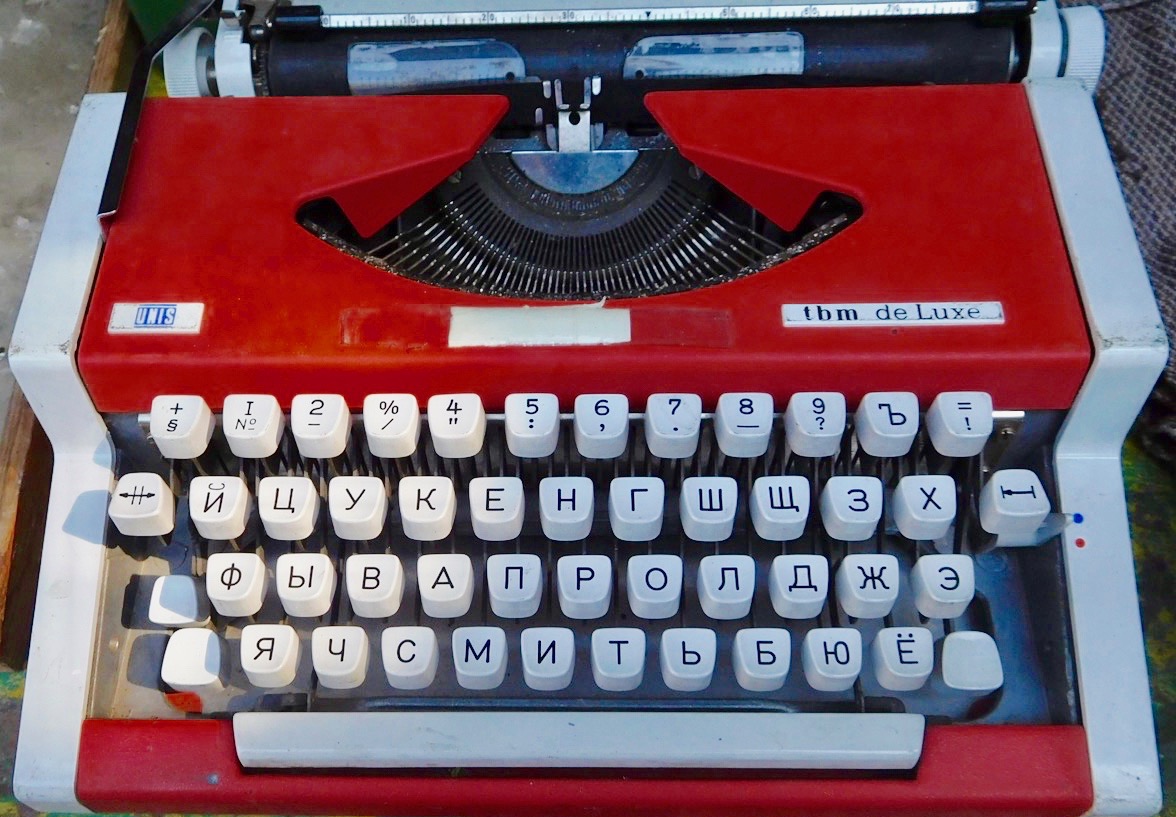

Its strategic position has brought it thousands of years of trouble. It has been invaded by Mongols, Persians and Turks. It was part of the Soviet Union for 70 years, finally seizing independence in 1991 as the USSR disintegrated after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Twelve years later, the last vestiges of Soviet leadership disappeared when President Eduard Shevardnadze was ousted in The Rose Revolution.

But it didn’t end there. In 2008, Georgia was embroiled in a five-day war with Russia and the Russian-backed former Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Eight years later, the borders to those separatist regions are still closed.

Well-meaning, if uninformed, friends had warned me of the dangers of travelling to Georgia. But in the whole ten days of the tour, which took us to within three miles of the Abkhazian border, I promise there wasn’t a moment when I didn’t feel entirely safe and comfortable.

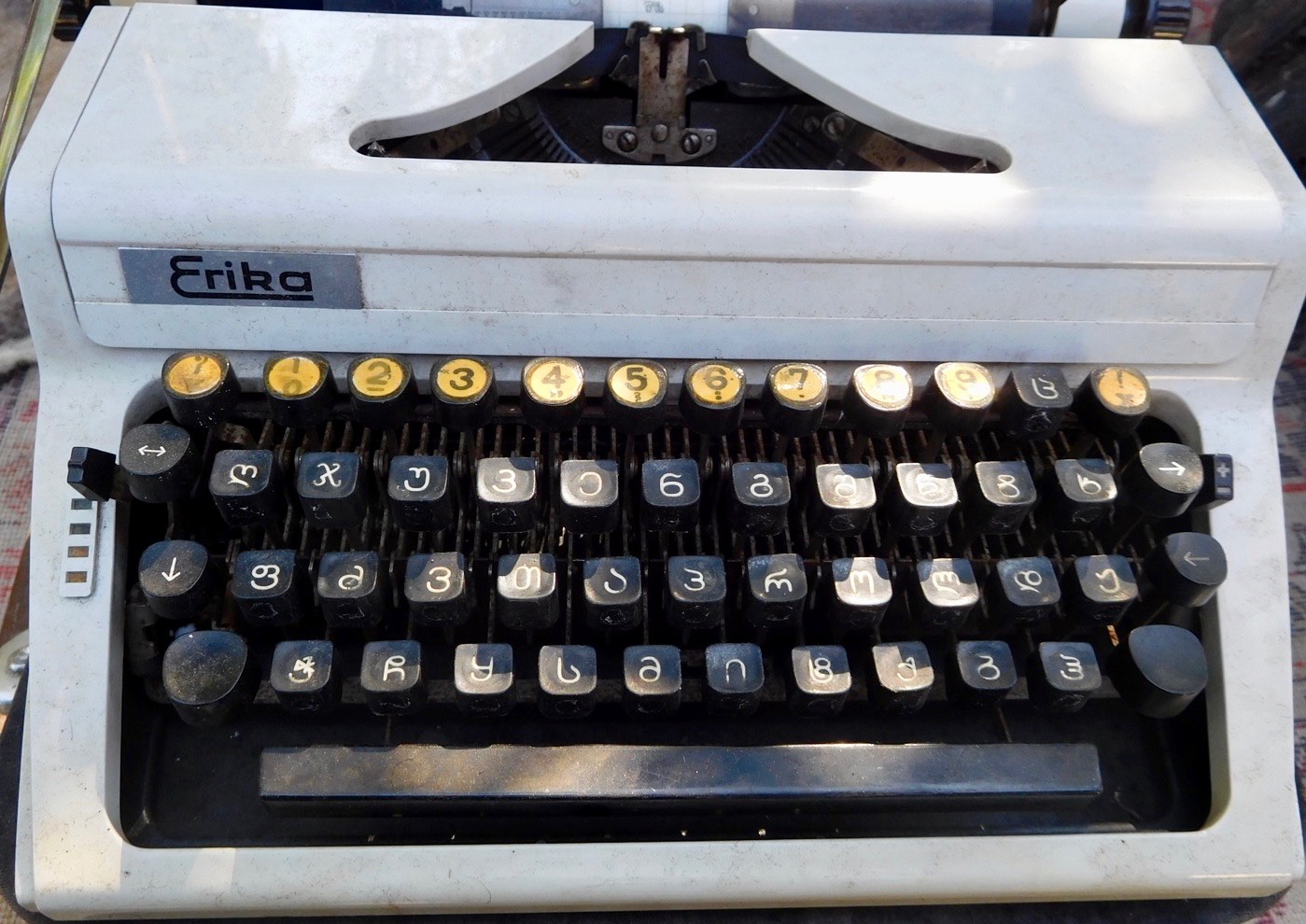

In part, that is to do with the people. Georgia has a population of just less than four million (not quite half that of London), and they are universally warm and welcoming, as well as fiercely independent, proud and passionate about their traditions.

In the Pheasant’s Tears restaurant in Sighnagi, a pretty dancer in her 20s explained in faltering English that she and her friends are not restoring or maintaining tradition – they are the tradition. These are our roots, she said. You have to have strong roots to support the weight of the fruit.

The group she is part of is called Zedashe, formed in the 1990s to perform the polyphonic chants unique to Georgia, which were largely lost during the Communist era. They joined us for dinner at a long table, and when they began to sing the noise they made stirred something deep: it brought real tears to my eyes.

Pheasant’s Tears is both the brand of a sophisticated and elegant restaurant, and a working vineyard. You can buy Pheasant’s Tears wine in the UK.

Wine making began in Georgia 8,000 years ago, and for Georgians the vine is the ‘tree of life’; as much part of the national identity as the Orthodox Christianity that has somehow evolved into more than a religion.

There are more than 500 different grape varieties in Georgia, with varietals changing from region to region. Georgian soldiers use to slip a cutting from a local grape vine into their tunics so that if they were killed and buried the vine would grow on that spot – a kind of resurrection.

In the beautiful Alaverdi Monastery in Georgia’s Kakheti region, monks have been making wine since 1011. And in the thousand years since they began, invaders have whitewashed the frescoes in the 11th Century Cathedral of St George, rooted up the vines and used the cathedral as a stable for horses.

And yet a full millennia later, a handful of monks are still making superb wine here using the traditional clay pots called Qvervri. The monastery has now become a tourist attraction, and the wine (in a nod to the monks’ resilience) is branded 1011.

Georgia was the world’s second Christian nation, having converted in 337AD, and the land is littered with churches and monasteries more than a millennia old.

On a couple of occasions, our animated guide Tamara Natenadze managed to get the key to a tiny church on the edge of a hamlet. And on each occasion the frescoes and icons were breathtaking; local work, often dating from the 11th and 12th centuries, and invariably moving.

More recent history is visible too. The long road between Batumi and Baku – on which the driving veers from chaotic to suicidal – is lined with Soviet-era concrete bus shelters, now often sheltering cows, which roam the lorry-laden highway in small herds. Elsewhere, there are abandoned factories, Soviet-era blocks of flats and, on one occasion, an unfinished bridge.

The Soviet legacy is actually being restored at Tskaltubo, a mineral-water spa in west-central Georgia created on Stalin’s orders for the Soviet top brass.

It’s a series of pavilions and hotels set in 16 hectares of parkland, and No 6 Spring is housed in a restored white Palladian style building, facing a glorious fountain.

Above the entrance, a smiling bas relief of Stalin, in white-on-blue Wedgwood colours, greets his people. Inside, treatments include ‘stimulation of the prostate and rectal tamponade’ and ‘gynecologic (sic) irrigation and a bath of mineral water’.

A few of us opted for a Sharko massage with high-powered water jets and a more conventional deep massage followed by half an hour in the mineral water pool that was Stalin’s favourite.

(Standing in nothing but a pair of blue paper pants, being hosed down by a nurse who appeared to find the whole thing very amusing, my principal emotion was one of profound embarrassment. But the dry-hands massage administered by a young Georgian woman with no English other than ‘turn over’ was wonderful.)

Stalin was, of course, Georgian, born in the town of Gori where there is still a large – and, for me, slightly disturbing – museum.

While we were touring the museum, a camera crew began filming us. Moments later, TV presenter Chris Tarrant walked in, and out, and in again.

Somebody told me he was shooting an episode of Great Railway Journeys of the World, focusing on the line from Batumi to Baku – although I suspect it was Stalin’s railway carriage in the grounds that had pulled in the production team.

From Mestia in the Svaneti region, we fought our way along 46km of unmade roads in a Mitsubishi Delice to reach Ushguli, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, 2,100m up in the shadow of Georgia’s highest mountain, Shkhara (5,068m) and close to the Russian border.

Ushguli is remarkable. It looks like a set from Game of Thrones; a timeless collection of cramped houses and defensive towers in an Alpine landscape. Some say it is the highest inhabited community in Europe, although a village in Dagestan on the other side of the Caucasus also lays claim to the title.

As we strolled through the ‘poop and mud’ of the villages (cows and pigs roam free), a small boy raced past us on a pony, stopping to execute showy and spectacular turns. He was riding bareback. We turned a corner and there was an ox cart loaded with hay, pulled by two placid oxen.

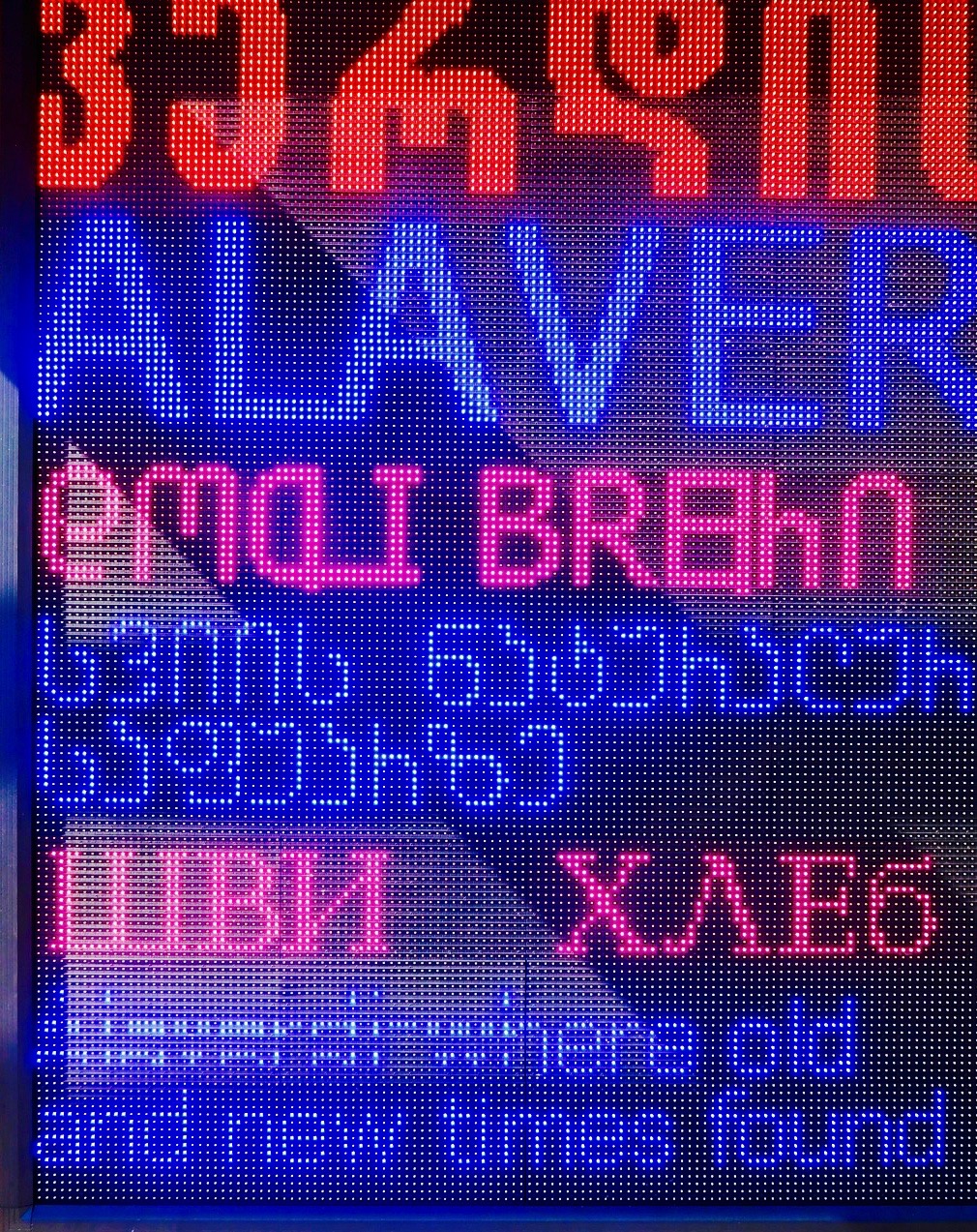

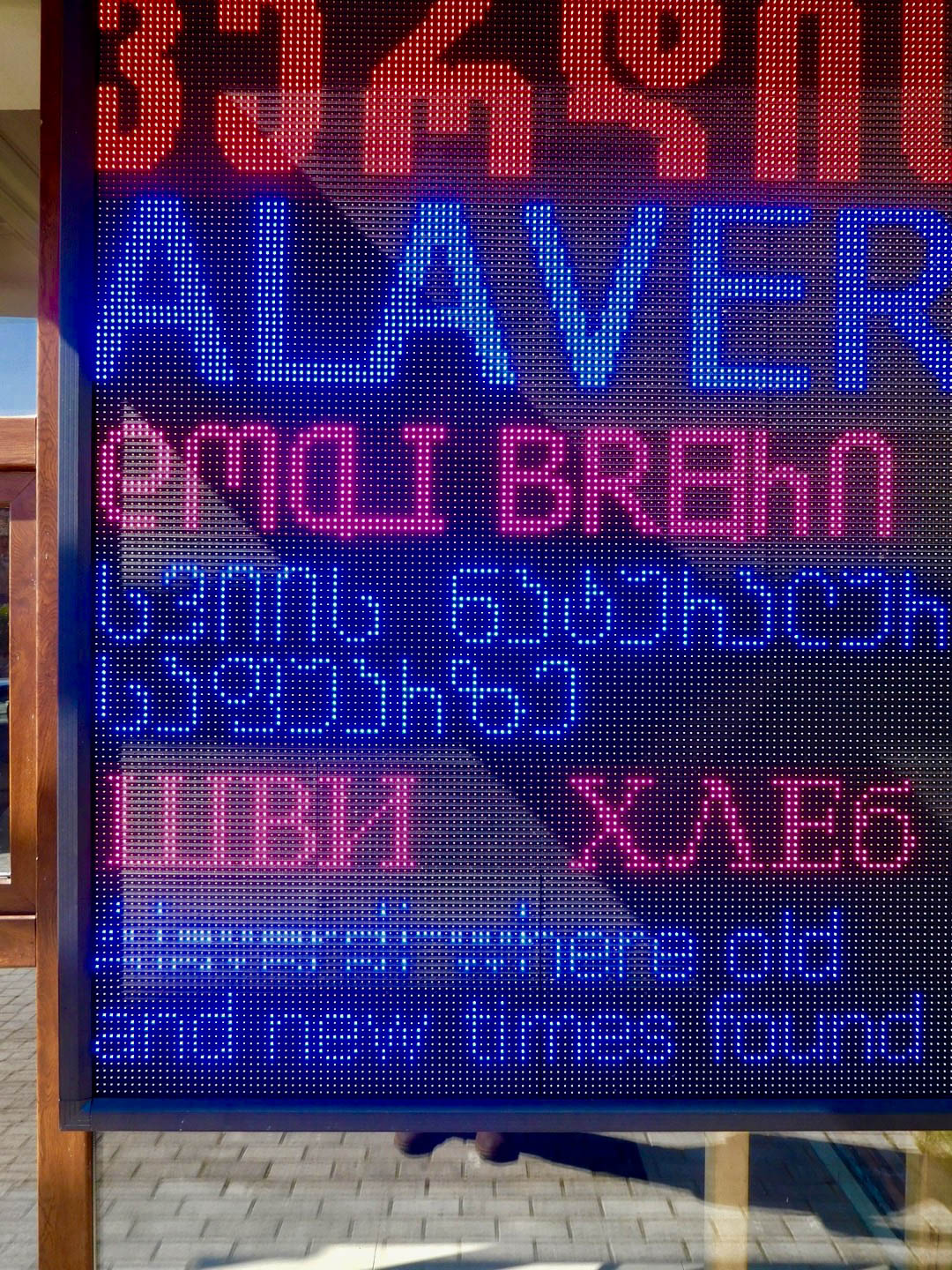

Tbilisi and Kutaisi – Georgia’s capital, and second town – are right at the other end of the scale. Tbilisi is über cool, a town of art galleries, restaurants and concert halls. Kutaisi feels so European it might have been in Spain or France, were it not for the neon-lit Tesco Georgia sign on the route between restaurant and hotel.

But it is Tbilisi that is, for me, the most surprising place in Georgia. Its old town is being carefully restored and is regaining its former dignity, while new buildings like the concert hall, the Public Service Hall and the Peace Bridge over the Kura River (lit by 1,200 LEDs) are among the most striking and controversial modern buildings in Europe. A new cable car now soars above the city, taking tourists from the new world architecture to the ancient fortress of Narikala above the old town. At night, the castle – and pretty much everything else – is floodlit and from a distance the city twinkles.

Georgia is one of the most remarkable places I have visited in what turns out to have been quite a long life. The food is wonderful (oh, those foraged mushrooms), the wine remarkable and the culture completely absorbing. I think I’m going to have Georgia on my mind for a long time yet.

* Our tour was organised by the excellent Tbilisi-based Living Roots (Living Roots website) and led by my friend Max Johnson (Max Johnson’s website) who has travelled to Georgia more than 20 times, and has now bought land there. You can hear Zedashe here: Zedashe on You Tube