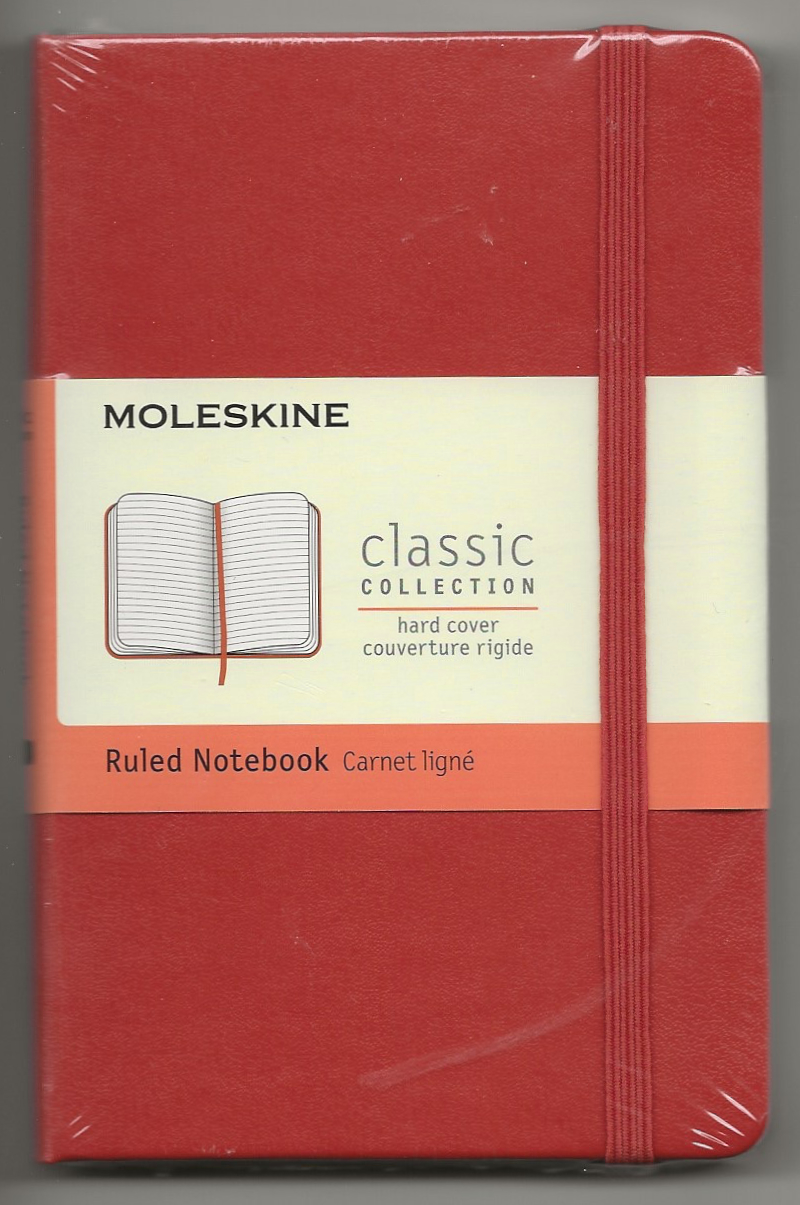

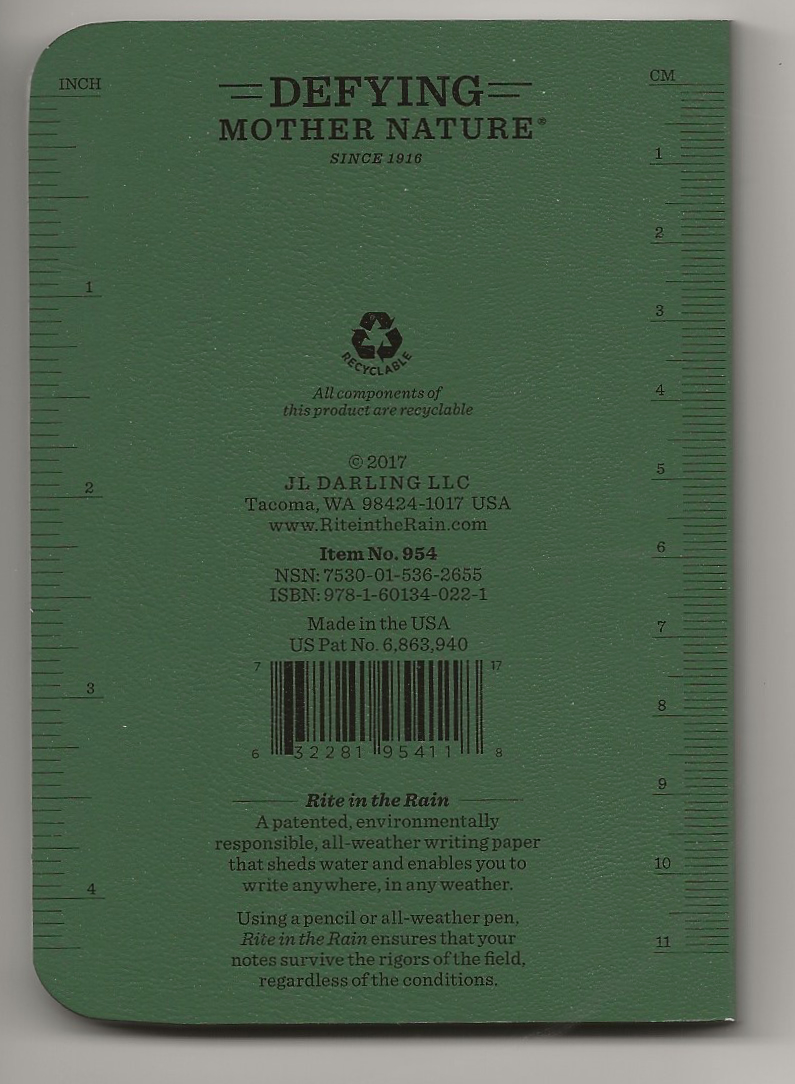

I WAS GIVEN another three notebooks for Christmas: a classic fiery orange Moleskine with elasticated binder and internal pocket; a beautiful little hand-designed, limited-edition black notebook from a friend who runs a graphic design company in Berlin; and - from my daughter, Lucy - an American Rite in the Rain All-Weather Memo Book, originally designed for woodsmen in Tacoma, WA, and perfect for damp birding trips in the UK. That one is the colour of beech leaves in mid-summer.

“I got another three notebooks for Christmas,” I said to Lucy on Boxing Day. “That’s okay,” she said, without looking up, “you love notebooks.”

She is right, of course. At this moment, I have around 25 ‘live’ notebooks in my study. They are all in use and while that may seem insane, there is more method than obsession in this madness.

To get this out of the way, I have kept a daily journal for the past nine years - although that is in digital form and online to facilitate searches. If a policeman were to ask me, “what were you doing on the night of September 29, 2010?” I would be able to tell him with an accuracy so startling he might not actually believe it.

In addition, I have an analogue bullet journal (explanation here), which is designed to keep my life in order, and to capture those things I might otherwise mislay - like a list of female Japanese authors, or Scandinavian jazz musicians, or really good value hotels near Kings Cross. That one is a brown leather Jasper Conran notebook with pen holder, and was a gift from my goddaughter.

Then there are the two commuting notebooks - one for each bag I use. They’re there so that I can capture random thoughts, record overheard conversations and make notes on authors, books, music, films and bits of technology I’m interested in, or quotations I like, or poems and stories I have ideas about. Pretty much anything really.

Often, those commuting notes are transferred to the bullet journal for safe keeping. And so I know that in 2004 I was walking through a furniture store in Tunbridge Wells when I saw a young couple staring glumly at an expensive bed.

“We’ll just have to bite the bullet,” the man said.

“There’s no bullet left,” said the woman flatly, “we’ve eaten it all.”

And on a train in January 2003, a young woman staring out of a window said: “I hate days like this. It’s as if the sun got up and couldn’t be bothered and just went ‘bleugh, have some sky’. It’s like seeing the sky in its dressing gown.”

Creative, funny and spontaneous dialogue like this should not be lost: the whole philosophy of the notebook revolves around the idea of ‘capture’. It’s a kind of literary photography: snapshots in words.

I have two notebooks in which I have recorded my travels around the planet. The first - another classic Moleskine (black) - was started in 2003 and remained in active use until 2017 when, in Espéraza in southern France, I left it on a balcony overnight. In the morning, it was soaked, expanded to twice its size and unusable.

It is still readable, though (now that it has dried out) and alive with curiosities - like the time I made notes in shorthand about the desperate inequalities I saw between victor and vanquished in a communist country. I wrote in shorthand just in case I lost it: I can barely read my own shorthand, I told myself, the authorities wouldn’t have a chance in hell. That one is a keeper.

It was also this notebook that made a solo trip to Venice more bearable. I had found a really cheap return flight to Venice Marco Polo airport at a time when I was desperate for a break. My wife was teaching and could not come with me. I remember my finger hovering over the ‘Continue’ button - and then impulsively pressing it, committing myself to a week alone in La Serenissima.

The trip was interesting, although, as I recorded in my notes: “Venice is a posh old tart, dressed up to pull in the punters. Look beyond the glamour, and she is fretful, needy and grasping.” It’s the personal view of a solitary traveller, of course. And I really was mercilessly ripped off on that trip.

One difficulty I had is that in Venice - an ostentatiously, almost comically, romantic city - if you are not holding hands with somebody by 9pm, you are viewed as lonely, or as an oddball. And so I had a few solitary dinners under the pitying or simply curious gaze of lovers young and old, until I discovered that if you make a lot of handwritten notes while you’re eating, the lovers, waiters and restaurant owners just think you’re a writer. And then it’s okay - Venice knows about writers.

My published travel writing rarely stretches beyond 1,500 words, but the observations and data collected in a single trip in scratchy Biro or felt-tip can reach 15,000 words and more. So my travel notebooks are valuable - to me anyway.

Then there are notebooks for specific projects - like the research I did for 18 months on a child slave brought from the Caribbean to England by the Master of a Man of War in 1764, a child who, once grown, became one of London’s best-known fops and a master fencer. That branched out, surprisingly quickly, into the lives of Handel, Robert Adam, Jane Austen, Adam Smith, William Pitt (the younger), Gainsborough, Johann Christian Bach, Samuel Johnson and many more. It is a treasured collection of notes, to which I return often. There’s something in there that is calling to me.

There is a notebook in which I make extensive scribbles about music theory, most of which I still struggle to understand; and another, smaller, leather Jasper Conran notebook I keep for observations on psychology, psychotherapy and sociology. There are, as I have said, many. My notebooks are legion.

A cardinal rule is that once a notebook has been dedicated to a particular project, it must never be used for anything else. While that may seem wasteful, it does mean that I know where everything is, and Elizabeth F Loftus’s observations on false memory are not lost in the notes I made recently for a piece on the history and lure of penthouses.

I appreciate, now that I have read through this blog again, that even with explanation this passion for notebooks may come across as obsessive. But, what the hell, I celebrate half a century as a journalist and writer next year - and when I started there was no way to digitally record anything. There weren’t even pocket calculators then, let alone Dropbox, Scrivener or Evernote. Notebooks were all we had - and you had to keep them for years, just in case there was a legal case (I always thought it odd that my barely readable shorthand could be accepted as ‘evidence’).

People who know me appreciate that I am, in fact, a bit of a techno-codger: I built this website; have a working knowledge of the recording software Cubase; and can more or less make Adobe InDesign work well enough to produce magazines.

But there are advantages to analogue notebooks. You can’t accidentally delete them; hackers can’t get into them; they actually survive a night in the rain (which a PC probably wouldn’t); and in the rapid world of social media they are a nice slow way of recording thoughts and observations without having to put them ‘out there’ for ‘likes’.

I am also a great supporter of the longreads and slow journalism movements: notebooks are their weaponry.

And for those of you who think that computers are so smart, I recently came across a computer game called Adventure of the Silver Blades in my garage. It included the floppy disks that were supposed to slip into one’s early iMac. For all but the most needy of nerds, they are now entirely useless - although the paper game journal is charmingly littered with pencil notes and explanations from my daughter, her best friend and me.

It’s also interesting to think that Charles Darwin’s notebooks from the Voyage of the Beagle (1831-1836) are still accessible. True, they are online - but that’s only because he kept analogue versions that have been digitised.

And writing, in longhand, in a really beautiful notebook is, when all said and done, therapeutic. Writing as therapy is a real thing, which I’ve studied a bit this past year - and to summarise all of my reading, without the attendant philosophy and psychology: Go ahead - start a notebook and see where it takes you.

My favourite - a Moleskine classic like the ones used by Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso.

A small wonder: the Rite in the Rain, all-weather memo book.